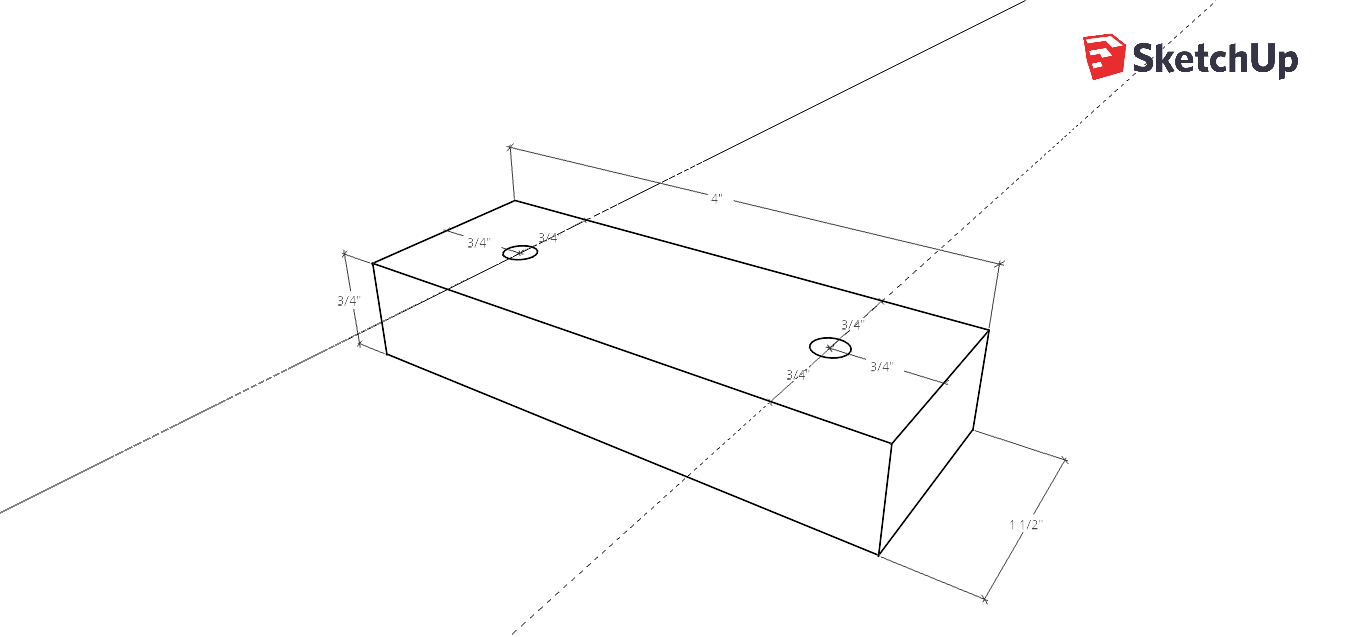

New research and a new tent stake! "Okay, we get it 1st Sgt. You have a weird obsession with Civil War tent stakes." I do! I believe this style of "Common Tent Pin/Stake" as referred to in the 1865 Quartermaster Manual is the closest I've come yet to replicating the Maple Leaf pins and common Civil War stakes in general. Still, few images exist of this type of once common tent stake. According to the Quartermaster Manual, the common pin should be 16" long, 1 1/4" wide, 1" thick, of defect-free white oak, with a notch 3" from the top. To make these, I used 3/4" red oak from the box store. 3" from the top, I drilled a 3/8" hole to be the end point of the notch. The notch is 2" long. I made a 3/8" hole for the hook of the notch figuring that would have been most likely the largest rope they would have used for tenting and would comfortably hook the loops on a "common" tent. The top, long slant is an angle of 3/8" from the edge of the stake down to 1 1/2". The small back slant is an angle of 1/4" to 1/4". The spear tip is 2" long tapering to 1/4" in the middle. I chamfered all the edges with a block plane for increased durability. It's hard to tell if the originals had an additional side taper on the spear tip or if they were just as shown. I've seen one just like I made. Either way, the manual doesn't specify.

These are really long tent stakes as you can see in the comparison photo. There are at least two more sizes listed in the manual. One being about 2' long! One of the longest having two notches that I imagine would have held the wall tent wall uprights as well as the fly ropes. These would certainly be overkill for a dog tent especially when compared to the relatively small turned oak pins that were initially issued. I think these would work great for a standard NCO wall tent or even larger. They'd also probably work well for tent flies.

I'll be posting more tent stake photos as I work my way through the Quartermaster Manual, though I have a growing stockpile of assorted period tent stakes that I don't know what to do with. I'm still quite fond of what I'll now call my "French style" oak tent stakes. The one the middle of the first photo. They fit very well with the styles of the time and would even fit into the camp-made category. They work well for securing A tents and dog tents. Just remember, when you use wooden tent stakes/pins be sure to use a wooden mallet!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed